,

June 30, 2021

A GHPIA client recently remarked to us, “I remember someone once saying about Congress, ‘Don’t tell them what comes after a billion.’ Someone did.”

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal debt was large by historical standards and is projected to rise.

Public debt is widely misunderstood. Although habitual use of public debt to generate artificially higher growth is ultimately problematic, more debt can be better than less in times of crisis, such as during the pandemic. When the economy is in freefall, rising debt levels can contain the collapse of company and personal balance sheets and foster recovery. Conversely, a failure to use fiscal policy helped pushed the U.S. economy into depression in the 1930s.

Nonetheless, we believe, despite the recent necessary spikes, investors should now watch debt levels carefully. There is often talk of “thresholds” – levels that will trigger a debt crisis or a slump in growth. While a desire for a simple metric is understandable, that is not how public debt works.

Despite the recent necessary spikes in government spending, investors should now watch public debt levels carefully.

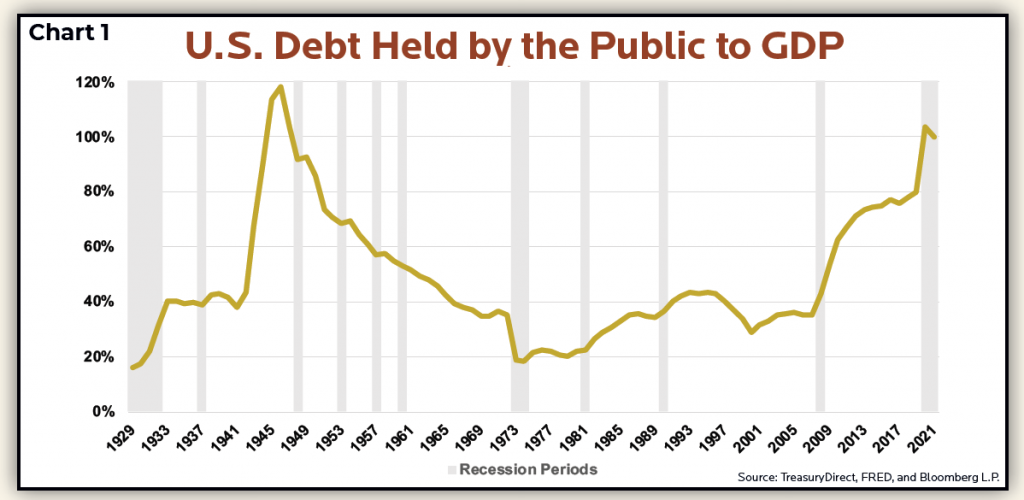

The national debt is approaching and may exceed the peak debt-to-GDP ratio of 120 percent experienced after World War II (Chart 1).

Does that mean U.S. debt is a current problem? Not yet. It is a mistake to use debt-to-GDP level as a primary measure of debt sustainability or indicator of debt risk. A better way to assess debt risk is to examine interest rates. Many economists think about the sustainability of national debt by considering the relationship between economic growth and interest expense.

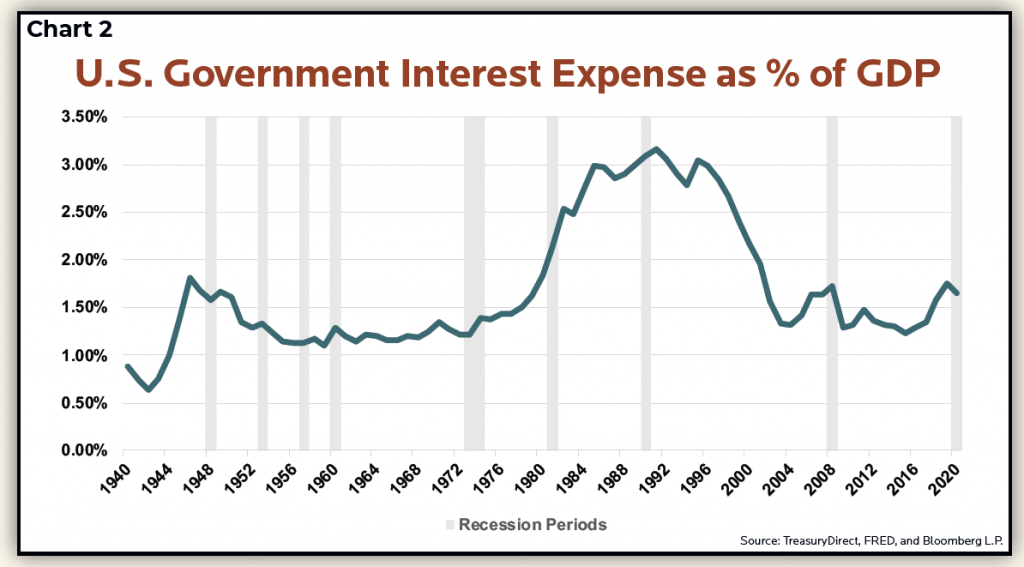

Even though our debt peaked in the 1940s, interest rates were low and economic growth was strong, making the federal debt burden manageable in the 1940s and 1950s. As you can see from the second chart, while our debt level peaked at the end of World War II, our debt burden did not peak until the 1980s.

At that time, interest rates stayed in double digits for an extended period even though our debt level was relatively low. When interest expense (often called the interest burden) reached 3% of GDP in the 1980s, bond investors became skittish about continuing to lend money to the federal government because interest expense consumed a material percentage of annual GDP growth in dollar terms. On a relative basis, however, the cost of servicing the national debt today is no worse than 10 years ago, and half of what it was half a century ago.

At that time, interest rates stayed in double digits for an extended period even though our debt level was relatively low. When interest expense (often called the interest burden) reached 3% of GDP in the 1980s, bond investors became skittish about continuing to lend money to the federal government because interest expense consumed a material percentage of annual GDP growth in dollar terms. On a relative basis, however, the cost of servicing the national debt today is no worse than 10 years ago, and half of what it was half a century ago.

If interest rates remain low, then, perhaps unfortunately, the federal government may continue to borrow and accumulate debt. Unlike individuals, the government lives in perpetuity and worries more about refinancing risk than repayment risk. As long as investors are willing to refinance outstanding debt and interest expense remains low, politicians face few constraints expanding the debt.

History suggests, however, that interest rates will not remain low forever. For the high level of debt to be sustainable, interest expense must grow more slowly than GDP in nominal dollars (real growth plus inflation) over an extended period. Otherwise, much of the growth in the economy accrues to bond holders in the form of interest payments. This has political implications well beyond just bond investor concerns.

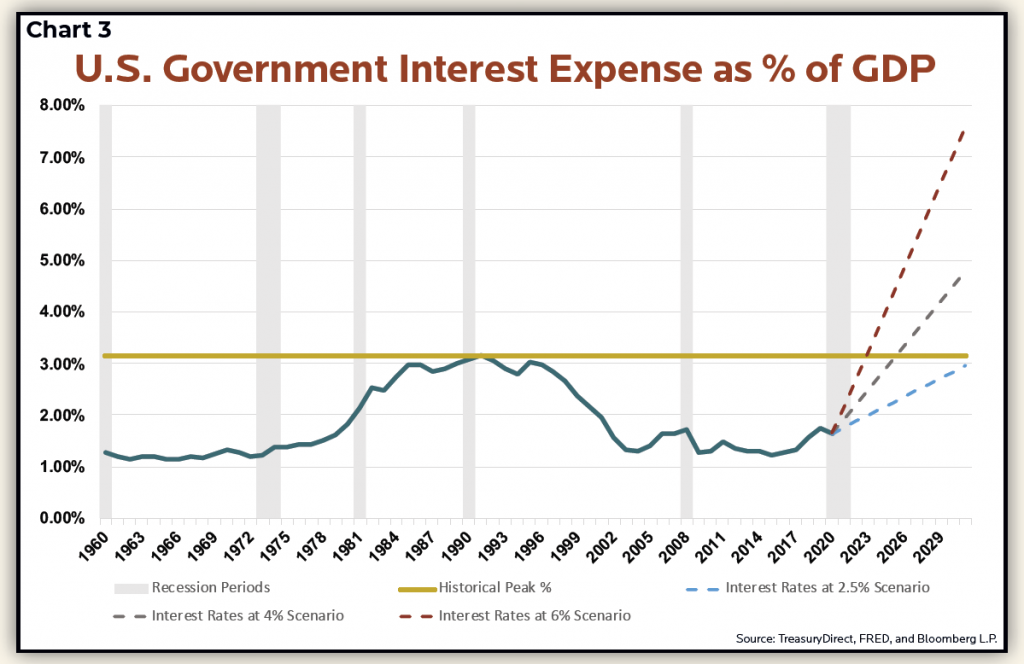

To illustrate, if debt-to-GDP peaks and remains at 120% and nominal GDP is 4% over the next decade, the national debt in 2031 will be $39 trillion. Chart 3 shows if government borrowing costs average 2.5%, the projected interest expense as a percentage of GDP is 3%. If interest rates instead average 4%, the interest expense to GDP percentage grows to 4.7%, and at 6%, the interest expense percentage is 7%. We expect bond investors to become increasingly concerned if interest rates exceed 2.5% (this is an average across all maturities) and if debt exceeds 120% of GDP. More broadly, fears will mount if interest expenses seem to be escalating faster than GDP growth, even as the post-pandemic economy normalizes.

If or when either event occurs, politicians will no longer be able to kick concerns about national debt down the road. In our analysis, it is highly likely the federal debt will accrue an interest burden similar to the 1980s even with modest interest rate increases. We suspect this upper limit of around 3% of GDP will once again prove to be a red line for the treasury bond market, as it was in the 1980s and early 1990s. Just like four decades ago, federal debt reduction will become a household topic. Most likely, the U.S. will strive to reduce its debt over time via tax hikes, slower spending growth, economic growth (increased GDP) and higher inflation. Slower spending growth is more likely and will also reduce debt-to-GDP as long as spending grows more slowly than GDP.

If or when either event occurs, politicians will no longer be able to kick concerns about national debt down the road. In our analysis, it is highly likely the federal debt will accrue an interest burden similar to the 1980s even with modest interest rate increases. We suspect this upper limit of around 3% of GDP will once again prove to be a red line for the treasury bond market, as it was in the 1980s and early 1990s. Just like four decades ago, federal debt reduction will become a household topic. Most likely, the U.S. will strive to reduce its debt over time via tax hikes, slower spending growth, economic growth (increased GDP) and higher inflation. Slower spending growth is more likely and will also reduce debt-to-GDP as long as spending grows more slowly than GDP.

For a further explanation of how we think of the investment risks associated with government debt, watch our latest video.

While the U.S. may experience a fiscal crisis, it does not guarantee an economic crisis. A fiscal shortfall is more likely to prompt an economic downturn if government debt levels contribute to the loss of market confidence in a national economy. As the wealthiest country in the world, with the dollar still maintaining its prominence as the world currency reserve, the U.S. has the capacity to shoulder higher debt. And that strength may extend to the stock market. Even with the high debt burden of 40 years ago, the S&P 500 Index returned 16.38% annually from 1980 through 2000.

The bottom line: the expansion of debt is troubling but not unexpected given our very low interest rates. Higher interest rates will likely check the debt expansion, but that is several years from now at the least. We lived through higher debt burdens before, and we managed the situation as a country and prospered. No need to call 911 about the U.S. debt yet.

For our analysis of the implications of international government debt for investors, read our latest Global Markets newsletter.

Investment Insight is published as a service to our clients and other interested parties. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.