,

March 31, 2022

The Federal Reserve’s (Fed) mandate is to promote maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. Yet you may have noticed recently that there is a disconnected labor market, large jumps in prices, and still historically low interest rates. So, one out of three, at least.

But not for long. The Fed has announced a plan to increase the federal funds rate, essentially increasing borrowing costs for everyone and helping to fight the increasing inflation we are all feeling in our pocketbooks.

Rising interest rates, especially after a long period of low rates and cheap borrowing, tend to spook investors. But the Fed’s actions do not necessarily mean the stock market is due for a collapse. On the contrary, history illustrates that the market typically performs well in a rising rate environment. Let us explain.

The Fed’s actions do not necessarily mean the stock market is due for a collapse. On the contrary, history illustrates that the market typically performs well in a rising rate environment.

The basic trigger of inflation is too many dollars chasing too few goods, causing prices to increase. We have seen many inflationary triggers in recent years. The easy monetary policies and robust fiscal policies in place during the COVID-19 pandemic supported strong asset prices and put extra spending money in American pockets. Since the pandemic, the Fed amassed more than $5 trillion on its balance sheet, more than doubling its size. This is well above the $3.7 trillion it added through the three rounds of quantitative easing between 2009 and 2014 to combat the Great Financial Crisis. The U.S. Government also contributed roughly $5 trillion in fiscal stimulus spending throughout the pandemic to help combat an economic downturn. With so much down time, social distancing, and government support, people’s personal savings rate increased dramatically during lockdown.

This excess capital increased demand for goods and ultimately drove up prices. With massive amounts of built-up demand and restrictions subsiding, consumers began spending. Used car prices are up over 41% over the past year. Gas prices are up 38%. Meat prices have risen 13%.

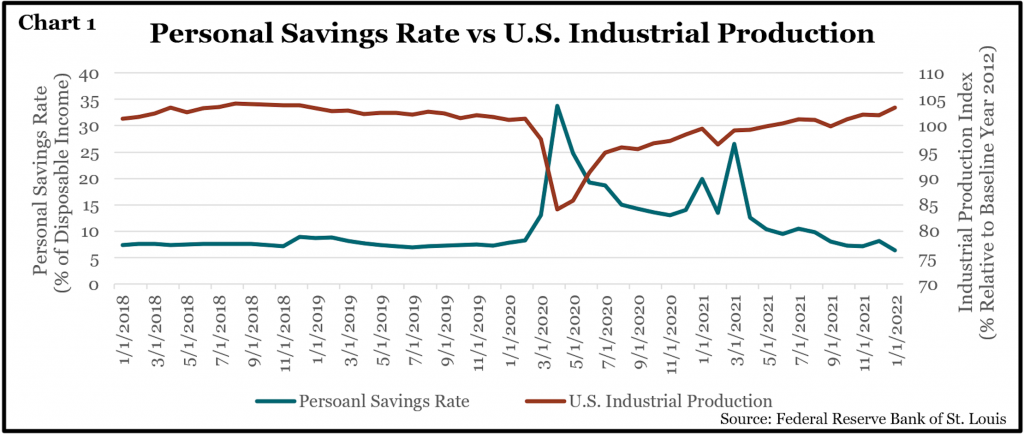

Despite high demand, many businesses not deemed essential had to shut down operations for a period during the pandemic. Many of you may have noticed that goods you were accustomed to buying were out of stock and, in some cases, no longer produced. That supply-side shutdown hurt supply chains, lowered production, and helped to push prices even higher. As Chart 1 shows, throughout the early months of the pandemic, during which capital was distributed to the American public, the personal savings rate jumped and then fell substantially once consumers felt comfortable to go out and spend. At the same time, U.S. industrial production fell due to the shutdown and then struggled to return to pre-pandemic levels. The combination of more money to spend and fewer products available contributed to the run-up in inflation.

To counter rising prices, the Fed is beginning to increase the federal funds rate, which is the rate at which commercial banks borrow overnight to meet their reserve requirement. This rate directly affects borrowing costs and determines what banks will charge on their loans. The higher cost is meant to deter borrowers from taking on more debt and encourage them to spend less. Debts such as mortgages, business loans, and car loans become more expensive, which can lead businesses to alter or pause plans for growth.

In theory, the Fed increases rates to slow down a hot and rapidly expanding economy, which puts the idea in investors’ minds that rising rates mean lower growth and therefore lower stock prices. Actually, stocks often rise during a rate hike cycle, since Fed action is often a response to vigorous economic growth. While higher rates will likely cause capital flows out of the equity market and into fixed income assets like bonds and savings accounts, not all stocks will be affected the same way.

Among the factors to watch, one is price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios or earnings yields, which are the inverse of P/E ratios. The earnings yield of the S&P 500 is currently 4.8% (the inverse of the current P/E ratio of 21), while the 10-year Treasury bond currently yields 1.9%. That means a 2.9% spread is compensating S&P 500 stock investors for the additional risk. If interest rates continue to increase, then companies trading at higher valuations could look less attractive due to a smaller or even negative spread. For example, suppose the 10-year Treasury bond’s yield rises to 3%. A stock whose P/E ratio reaches 35 has an earnings yield of 2.9% (1/35) and would therefore appear less attractive than the Treasury bond. In this scenario, it would make more sense to buy fixed income or securities with much lower valuations.

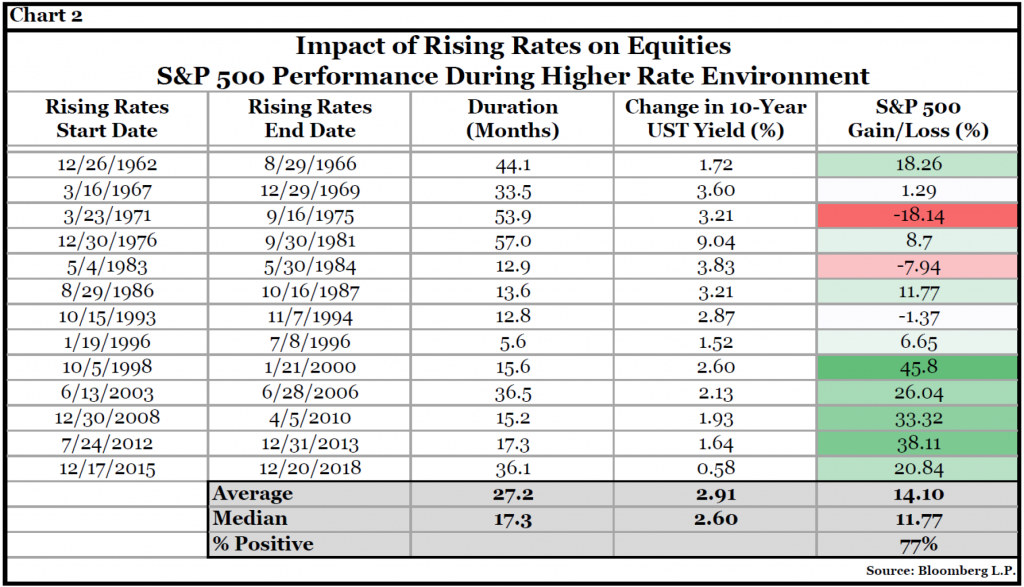

History shows that a rising interest rate does not mean stocks decline in value — with a few notable exceptions. Equities have performed well during periods of rising rates, as shown in Chart 2. Since 1962, 10 of the past 13 rate hike periods have experienced a positive return in the S&P 500, or 77% of the time. During these 13 periods, the S&P 500 averaged a 14.10% return.

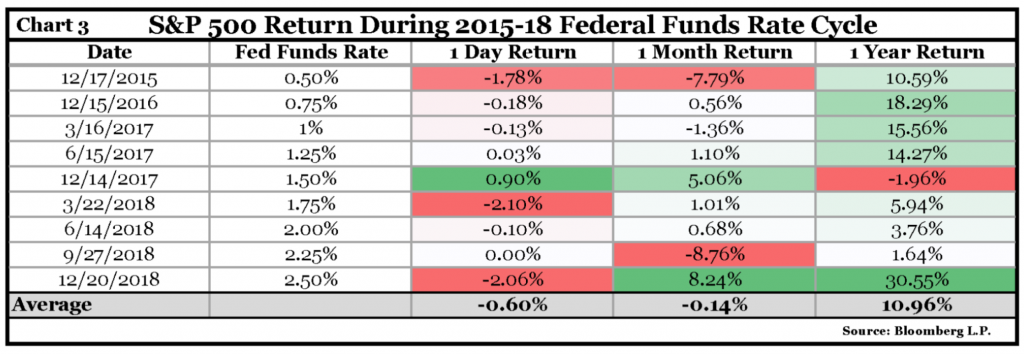

This is not always the case in the short term. As shown in Chart 3, during the last Fed rate hike cycle, from December 2015 to December 2018, the 1-day return average was -0.60%. The 1-month return after a hike was -0.14%, and the 1-year return was 10.96%. This information is inconclusive, and we still expect plenty of market volatility, but for long-term buy-and-hold investors like GHPIA, the evidence is clear: Fed rate hikes are not necessarily bad for the stock market.

By no means are we claiming that, just because historically the market has risen during a rate hike cycle, it will do so again this time. There are many more factors at play at the moment, such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine – triggering a potential energy crisis – the economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, and the historical shocks that the economy experienced. Although it may take some time, we anticipate the economy will continue to normalize as supply chains open back up and industrial production returns to pre-pandemic levels.

Rate hikes do not affect every sector equally. For example, during a rising rate environment, financial stocks, like banks, tend to perform better because higher rates mean higher margins. The opposite is true for companies that borrow to fund operations. Rising rates can mean more money going to finance debt instead of growing the business and taking on new opportunities.

This is one instance where diversification really helps. In a well-diversified portfolio, some stocks will be down in the short run while others will be up. Rather than trying to time the market and make trades based on anticipation of what the Fed and the economy will do, we prefer to buy an array of companies that are sector-diverse, reasonably valued, and have good cash flow. Such companies are likely to be good long-term investments, no matter if rates are rising or falling.

At GHP Investment Advisors, we work to remove the short-term noise and worries for clients. We invest in companies that our research indicates have strong fundamentals and prospects for future growth. There will always be short-term ups and downs, but our analysis suggests that trying to time them, even in response to significant economic indicators such as Fed rate hikes, can be futile and even counterproductive. We prefer to ride out market volatility by remaining invested in well-established, well-run companies.

Investment Insight is published as a service to our clients and other interested parties. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.