,

September 30, 2020

If you have ventured out lately, you may have noticed restaurants that are only a third full, and many closed shops. But what you might not have realized is that the curtailed retail activity from the COVID-19 pandemic also means less revenue to the local and state governments, possibly imperiling the future of your community. If you are a municipal bond investor, it may also affect your portfolio.

Despite its reputation for safety, the municipal bond market has not been spared the volatility that has rocked other markets. Earlier this year, yields surged in the municipal bond market as panicked investors tried to cut their losses. While the Fed’s intervention helped stabilize the market, the lockdown’s economic impact may result in state and local bond issuers struggling to maintain payments.

State and local governments generally issue municipal bonds to raise capital for infrastructure projects. Issuers pay interest generated from current property and sales tax revenues. For investors, the appeal of these bonds, which typically pay a specified amount of interest semiannually, is that the interest is free from federal income tax. If the bondholder lives in the municipality that issued the bond, the tax savings may extend to that state. The potential tax advantages often result in higher effective yield compared to corporate or other types of bonds.

During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, municipal yields rose as worried investors began selling their positions. The inverse relationship to yields caused municipal bond prices to fall, which in turn increased the selling. After this dramatic price drop in March, the municipal market just as quickly returned to pre-pandemic highs. At GHP Investment Advisors (GHPIA), we worried that the return to normal was premature, given the potential for large revenue losses to states and cities resulting from the ongoing lockdown. Rather than returning assets to the bond market based on increased yields, we believed a deeper analysis of risks in the market was warranted.

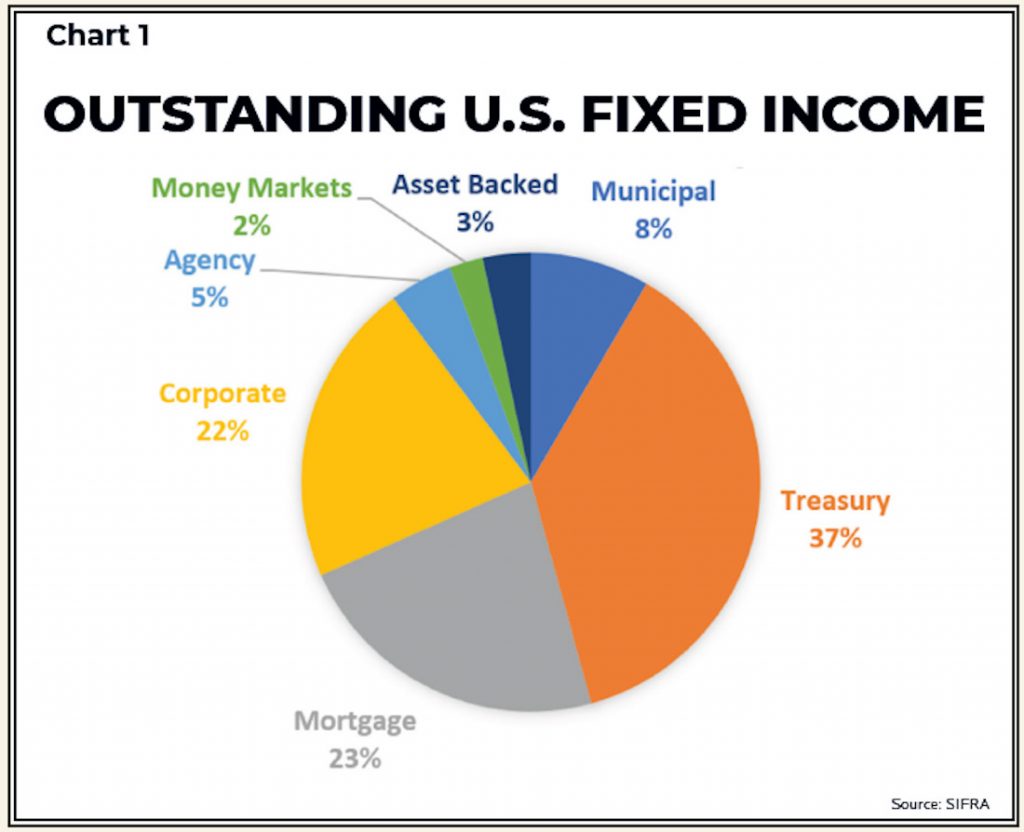

During the municipal market selloff, the Federal Reserve stepped in and began buying municipal debt in what is known as the Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF). They did so to help state and local governments alleviate cash flow pressures and continue to serve local households and businesses. The MLF plan was to purchase up to $500 billion of short-term notes directly from states to help maintain the $3.9 trillion-dollar municipal bond market. This is unprecedented territory for the Fed, which had never entered the municipal bond market. The Fed will have to tread lightly in its purchasing, as the central bank’s balance sheet is roughly the size of the entire municipal market, which in turn comprises 8% of the overall U.S. bond market (see chart 1). Too much purchasing could distort the natural flow of the municipal market.

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, states will need another $555 billion through June 2022. The National League of Cities, an advocacy group for cities, towns, and villages, says cities and towns will need another $360 billion through December 2022.

Despite dim prospects for local aid, municipal bond prices have continued to rise. Among small municipal bond issuers, defaults are on the rise, as the gap between public spending and revenue is unsustainable. The National League of Cities estimates total revenue losses for cities and towns could reach $134 billion in 2020, representing an 8% decline from 2019, forcing municipalities to lay off and furlough employees, slash spending on capital projects, and severely cut services. Unfortunately, these actions could come when communities need services most and could put greater future fiscal burden on taxpayers.

At GHPIA, when we speak with municipal bond issuers and other municipal bond managers, we often hear the same things – they have a AAA rating (the highest rating possible), they are in a state that has historically paid its debts, or their bonds are only slightly riskier than treasuries. Although this is relevant information GHPIA uses to evaluate municipal bond risks, it only scratches the surface.

We approach municipal bond analysis the way we analyze individual stocks. Like publicly traded companies, municipalities must issue annual financial statements. As with stocks, we look at the income statement to evaluate the operating risk. We evaluate the municipality’s cash flow and determine if its income is sustainable and steadily growing or volatile and at risk of deteriorating. We compare that income to the annual expenses the municipality pays out. We also consider its long-term debt, such as pension obligations.

Municipalities typically earn income in two ways: sales tax and property tax. As with a business or household, if a municipality’s expenses are more than their income, problems may arise. In fact, even before the pandemic, some municipalities already faced potentially horrific revenue shortfalls. For example, Illinois entered the pandemic with a reserved savings, also known as a rainy-day fund, of only around $4 million, amounting to less than 0.0001% of its budget. The state had almost no savings to help cover its current bills, let alone its unfunded pension liabilities and backlog of unpaid bills. On the other hand, such states as South Dakota, Idaho, and Wyoming had rainy day funds amounting to a year’s worth of annual revenues. Colorado had a $1 billion rainy-day fund, amounting to about 8% of expenditures.

Looking at the overall debt level helps us determine if the municipality will be able to pay future interest payments and principal at maturity. If the municipality is continually borrowing to keep up with current expenditures and not for the community’s future growth, then it could be in serious trouble. During this crisis, we evaluated the cash on hand that each municipality in our bond holdings reported. By breaking down annual expenses into daily expenses and comparing those to daily cash on hand, we could see how long a municipality could ride out the lockdown. For example, we estimated that Denver International Airport (DIA) had more than 700 days of cash on hand. Although it had originally raised some of this cash for projected renovations, we still felt this was a benefit and that DIA could continue to operate even though, according to TSA numbers, airport traffic was down as much as 90%.

A municipal bond’s sector or industry is also relevant. Bonds for higher education, health care, and tourism/travel have had their creditworthiness tested. Massive revenue losses in these sectors cast doubt on whether municipalities will be able to continue making debt payments on outstanding bonds and on whether they will maintain the creditworthiness to borrow more in the future. Such tourism-dependent cities as Las Vegas and Honolulu have recently seen their bond ratings lowered due to travel restrictions and social distancing regulations. Also, colleges and universities have begun to feel the effects of the pandemic on their room-and-board revenue streams, with many students not returning to school and opting for virtual learning.

On the other hand, bonds in such areas as housing finance and utilities have felt much less impact. These services are considered essential and have a diverse customer base, leaving them better insulated from COVID-19’s economic gloom.

To be clear, we are not suggesting that municipal bonds are a bad investment. On the contrary, municipal bonds remain a relatively safe place to hold capital while taking advantage of tax benefits. Some cities and towns may have started to default, but since the 1900s, only one state, Arkansas in 1933, has defaulted on its bond obligations. Rating agencies Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s still show 15 states as having a AAA rating. And the consequences of default aren’t necessarily dire. Per U.S. bankruptcy law, states are not allowed to file for bankruptcy. Municipalities can file for chapter 9 bankruptcy but must prove they are insolvent and have made a good-faith attempt to negotiate a settlement with their creditors. The result may be a renegotiation of terms with bondholders that creates modest losses in principal or interest.

The challenge for investors is determining which municipalities will withstand this economic stress and which will falter. Individual investors, advisors and investment professionals should dig deeper into the “safe” part of portfolios and decide if the risk of individual bonds is worth the reward. If we are your advisor, then be assured we are doing so.

Investment Insight is published as a service to our clients and other interested parties. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.