December 31, 2014

Money makes the world go round and borrowed money makes it go faster. The Federal Reserve (the Fed) is all too aware of this and controls monetary policy by adjusting the rate at which banks lend money to each other, called the Federal Funds Rate. This one lending rate influences borrowing costs for Uncle Sam and for you. On December 16th, 2008 the Fed lowered this rate to zero and has kept it there ever since. As a result, we have enjoyed low borrowing rates for credit and mortgages. The trade-off is that if you are a saver, bank CDs and bond yields remain at historic lows. The Fed now indicates this policy is likely to end in 2015. We are looking forward to when the Fed finally raises interest rates. Why? Put simply, it means that in the Fed’s estimation the U.S. economy is doing well. Their concern will shift from boosting economic growth to controlling inflation. Even better, our clients will start earning a more appropriate return on their hard earned money when investing in the bond market and CDs. However, broad expectations of rising interest rates do not ensure their occurrence. The Fed has been thwarted in the past when attempting to increase long term interest rates and similar factors face them again.

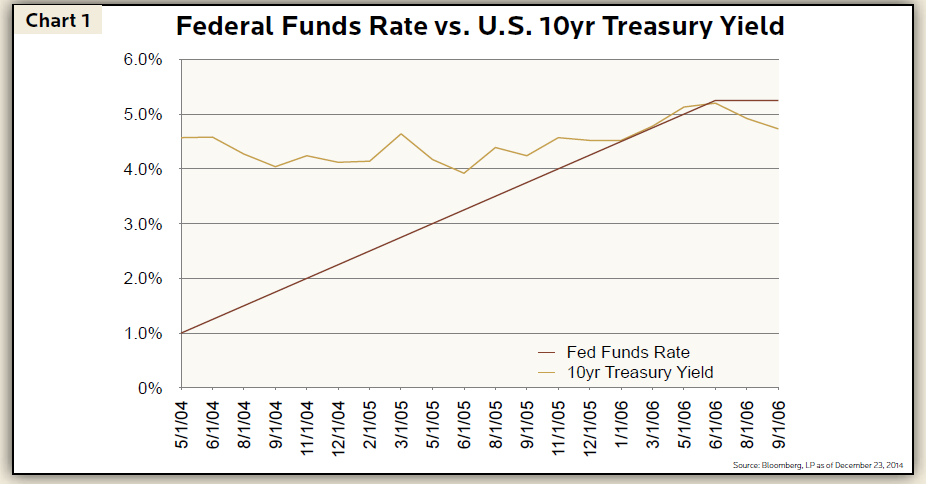

Leading up to the financial crisis, the Fed was on a course to raise interest rates to set the U.S. economy on a sustainable path. The year was 2004 and the Federal Funds Rate was at 1%. Alan Greenspan was the Fed Chair at the time. With well communicated intent, the Fed began to methodically raise interest rates a quarter of a percent at each Fed meeting. In June of 2004, the yield on the 10-yr Treasury had been as high as 4.87%. By June of 2005, the Fed had raised the Federal Funds Rate to 3.25%, an increase of 2.25%. In contrast, the yield on the 10-yr Treasury had fallen to 3.89%, a decline of nearly 1%. These lower long-term interest rates helped exacerbate the mounting housing bubble. In congressional testimony in 2005, Greenspan called this a “conundrum”. Ben Bernanke, who would go on to take the reins from Greenspan in 2006, credited this decline to a “global savings glut”.

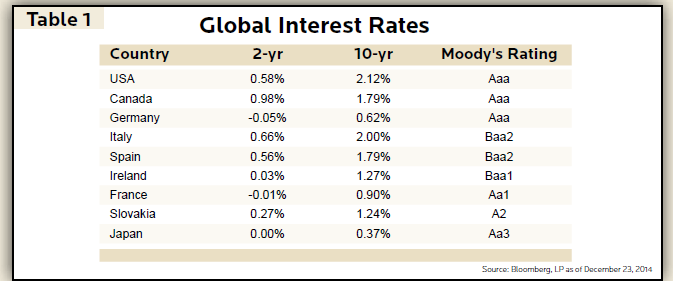

Today there exists another savings glut as global investors have driven down interest rates around the world. Germany has been experiencing negative interest rates on their shorter maturity government bonds and the German 10-yr government bond yields less than 1%. Other countries with credit ratings below that of the U.S. are also experiencing lower long term interest rates. Ireland, whose credit rating is seven notches below the AAA rating of the U.S., has a 10-yr government bond that yields more than a half of a percent less than the U.S. 10-yr which is above 2%. Even a tiny country like Slovakia has interest rates below those of the U.S. As you can see, as paltry as U.S. interest rates may appear to you and me, to foreign investors these must look like bargains.

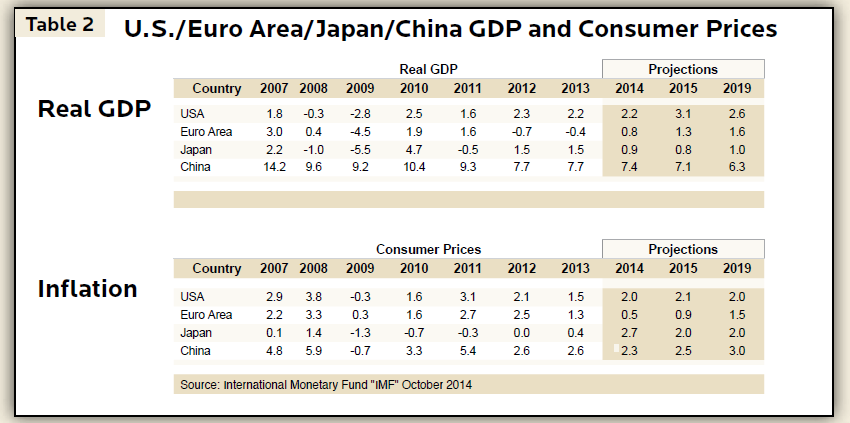

Slower global growth may caution the Federal Reserve against raising interest rates out of concern that we might fall into the same slump as our trading partners. Looking at GDP and inflation projections for 2014 and 2015 as prepared by the International Monetary Fund, we find again that while nationally growth in the U.S. is far from robust, it is better than both the Euro Area and Japan, meanwhile China is decelerating.

We also must consider what motivates the Fed. The Federal Reserve has a dual mandate; in 1977 Congress amended the Federal Reserve Act, stating the monetary policy objectives of the Federal Reserve as:

We also must consider what motivates the Fed. The Federal Reserve has a dual mandate; in 1977 Congress amended the Federal Reserve Act, stating the monetary policy objectives of the Federal Reserve as:

“The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Open Market Committee shall maintain long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates.” [source: ChicagoFed.org]

The Federal Reserve seeks to maintain stable prices, meaning low inflation while encouraging maximum employment, think “low unemployment rate”. It is a delicate balancing act, one where the winds of world events and the global economy are constantly blowing in different directions. The oil price collapse that began in October 2014 is an example of the many variables the Fed must interpret and anticipate the resulting economic impact. The decline in a core commodity can be both deflationary and economically stimulating. Inflation is averaging 1.40% in 2014, well below the Fed’s stated target of 2%. From 2000 through 2007 inflation averaged approximately 1.89%. Since the financial crisis it has been even lower, averaging 1.54%.

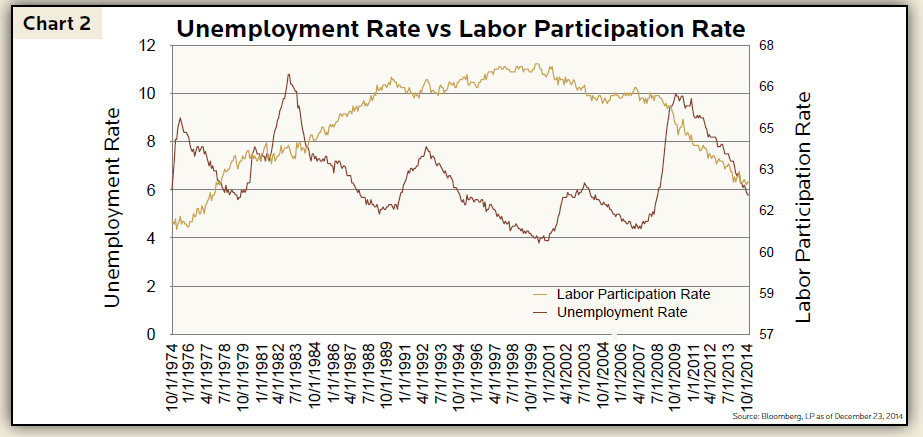

Looking at jobs data we find that metric is less black and white. While the widely quoted Unemployment Rate peaked at 10% in 2009, it has since fallen to an impressive 5.8% as of October 2014. However, the Labor Force Participation Rate – which reflects the percentage of the working age population with a job – hovers around 63%, down from the pre-financial crisis high of 67.3%. We have not witnessed such a low participation rate since early 1978. Looking at the unemployment rate and the rate of inflation, it is doubtful the Federal Reserve will be compelled to drive interest rates substantially higher.

Monetary Policy is a delicate balancing act. Like Goldilocks, an economy that is “too hot” can generate excessive inflation whereas an economy that is “too cold” fails to create meaningful employment. The Federal Reserve must get it “just right” and a lot is at stake if the Federal Reserve gets it wrong. For example, we witnessed the “Taper Tantrum” in the second half of 2013 when Fed Chair Bernanke suggested that it might be time to taper the Federal Reserve’s monetary expansion to wind down quantitative easing. This led to a “tantrum” in the bond market that drove the yield of the 10-yr treasury from 1.63% to just above 3% between May and December 2013. One could argue this contributed to the plunge in U.S. GDP in Q1-2014 of -2.1% when the preceding quarter had been +3.5%. With so much at stake, Fed Chair Janet Yellen may opt for an extension of the status quo rather than rocking the boat and risking a capsizing of the economy.

For our clients, we continue to take a cautious approach to interest rate sensitive investments. We are constantly monitoring the markets, vigilantly seeking valuations that are in alignment with our benchmarks. Entering the new year, interest rates remain at historically low levels. This is a boon for borrowers. However, for investors, many short term bond yields are below the rate of inflation and long term bond yields are not much higher. When your return on investment is less than the rate of inflation, you are effectively losing ground.

As we enter into 2015, many expect the Fed to raise interest rates. Many expect long-term yields to be significantly higher. The Fed itself has indicated they may be in a position to raise rates in 2015. As bond investors we are hopeful this will occur. However, when reviewing all of the many inputs that go into the Fed’s decision it appears doubtful they will raise rates meaningfully higher. Furthermore, even if they do they may be frustrated to find that long term yields may be resistant to change. Simply wishing for higher yields does not make it so. For those desiring materially higher bond yields, 2015 may bring more frustration.

Investment Insight is published as a service to our clients and other interested parties. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.