,

June 30, 2019

Although the eurozone has enjoyed continuously declining unemployment in recent years, both economic growth and inflation remain stubbornly low. With negative interest rates over the last five years and a recently exhausted campaign of quantitative easing, European Central Bank (ECB) monetary policy influence will be limited going forward. This shifts the burden to stimulate growth to fiscal policy and structural reform measures.

A recent example of such pressure occurred during the annual meeting of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) this April. Global central bank governors and economists argued that Germany – boasting the largest economy in the eurozone – is in a position to provide fiscal stimulus but has instead opted to maintain a flush budget surplus. While Germany clearly has the fiscal capacity to boost growth by either increasing spending or cutting taxes, historical context explains why it currently remains reluctant to pursue these options, despite the mounting entreaties from the IMF.

Germany finished 2018 with a record budget surplus of €58 billion ($65.8 billion USD). This was the fifth consecutive year Germany enjoyed such a surplus. However, as global trade slowed, and Germany’s auto industry encountered numerous troubles, the country narrowly averted a technical recession (two consecutive quarters of GDP decline) at the outset of 2019. With such precarious economic conditions, most countries would consider running a budget deficit with the aim of providing stimulus. However, German finance ministers harken back to the 1920s and cite the ruinous impact of German hyperinflation then as reinforcement for current budgetary conservatism. In fact, they even have a term for such conservatism, Schwarze Null, or “black zero”, meaning a balanced budget or budget surplus (“in the black”).

With the Treaty of Versailles marking the end of World War I in 1919, Allied powers imposed massive war reparations on Germany. Under the burden of these unaffordable reparations, the German Weimar Republic began printing money, which devalued its currency (marks) and triggered inflationary pressures. In 1921, as Germany continued to struggle to keep up with reparations, the Allied powers imposed a more draconian payment plan, demanding only gold or foreign currency payments. In response, the German government engaged in mass printing of bank notes to buy foreign currency to make reparation payments. This vicious cycle caused the mark to devalue further and, ultimately, one of the worst instances of modern economic hyperinflation ensued. For example, in 1919, a loaf of bread in Germany cost less than 1 mark, but by late 1923, the cost rose to an astonishing 100‐billion marks. Famous images from this era capture Germans carrying marks in wheelbarrows or using them for wallpaper and kindling. Tragically, this financial devastation also led to German public support of extreme political parties and the rise of fascism.

As generations of Germans passed down the harsh lessons from this catastrophic era of hyperinflation, debt and deficit became anathema. For example, Germany has the lowest homeownership rate, at 51%, of all countries in the European Union, a figure far lower than the U.S. at 64%. During the lead‐up to the Financial Crisis, most wealthy economies witnessed an increase in household debt as a percentage of income, while this ratio declined in Germany. Rather than run up credit card balances that stay outstanding for months, Germans use direct debits for more than 50% of their card transactions, a figure far greater than any other European country’s. During this time, the ECB kept rates negative in an attempt to stimulate borrowing, thus proving just how difficult it is to break a 100‐year‐old German discipline staunchly in favor of cash over debt.

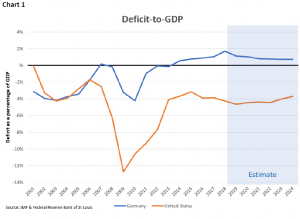

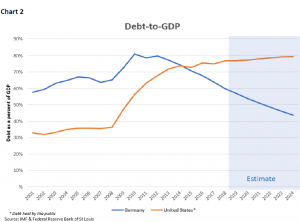

Just as German individuals continue to exercise caution with debt and deficits, the German government is likewise managing debt with resolute conservatism. In the years following the Financial Crisis, the contrasting fiscal policy between Germany and the U.S. has been stark. In 2006, the U.S. government ran a budget deficit of roughly 1.7% of economic output (GDP), while U.S. debt sat at 36% of GDP. In Germany these figures were 1.7% and 66% respectively (see Charts 1 and 2).

Today the U.S. budget deficit is 4.5% of GDP, with debt at 77% of GDP. Meanwhile, German fiscal austerity produced a budget surplus, and debt‐to‐GDP steadily declined to 57%.

Future IMF projections of these figures show even wider divergence. While German fiscal policymakers remain wary of running looser budgets despite their sputtering economy, deficit hawks in the U.S. seem to be an endangered species, as political support for reducing the debt has waned in recent years.

Germany’s most recent annual GDP growth was a feeble 0.7%, the weakest growth rate since the ECB implemented negative interest rates. As Germany produces nearly half of its GDP from exports, the recent decline in global trade has hindered growth.

This June, the ECB signaled further rate cuts are likely (deeper into negative rate territory), as most of Europe, along with Germany, finds itself once again in a fragile economic state. The ECB’s ongoing five‐year experiment of negative rates has fallen short of its original goal to boost economic growth and inflation across the euro area. Therefore, in the months ahead, the IMF is likely to escalate political pressure on German leadership to implement fiscal stimulus, as the country’s capacity to safely increase debt and deficit spending is clearly comfortable. If Germany elects instead to stick with its 100‐year ethos of Schwarze Null, it will at least have a fiscal policy toolbox offering more latitude than more indebted governments, such as the U.S., if a recession hits.

Investment Insight is published as a service to our clients and other interested parties. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.