,

November 20, 2023

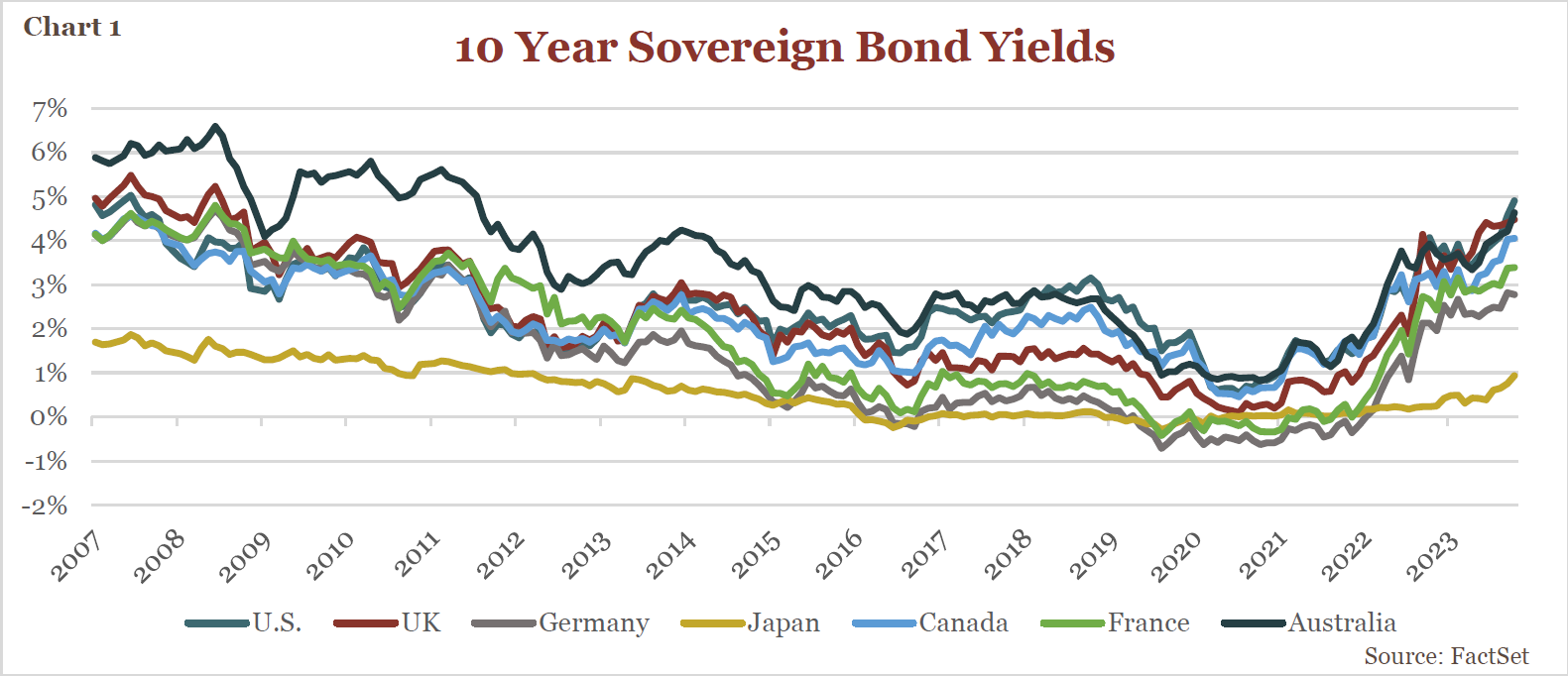

After spending much of the past decade below 2.5%, the yield on the U.S. 10-year Treasury bond briefly touched 5% in late October, its highest level since July 2007 (see Chart 1). Simultaneously, interest rates across the globe demonstrated a parallel trend with Canada’s 10-year government bond also revisiting 2007 levels, the UK 10-year gilt yield hitting its highest level since 2008, and 10-year German, French, and Australian sovereign bonds reexploring 2011 heights. Even long-term Japanese yields moved higher. While the absolute level of interest rates is important, often the speed of the fluctuations can provide us more discerning insight into the prevailing economic dynamics.

To understand the recent increase in long-term government bond yields, an examination of underlying fundamental determinants is required. Amidst a plethora of contributing considerations, notable factors include inflation expectations, monetary policy, fiscal policy, economic growth, and market sentiment.

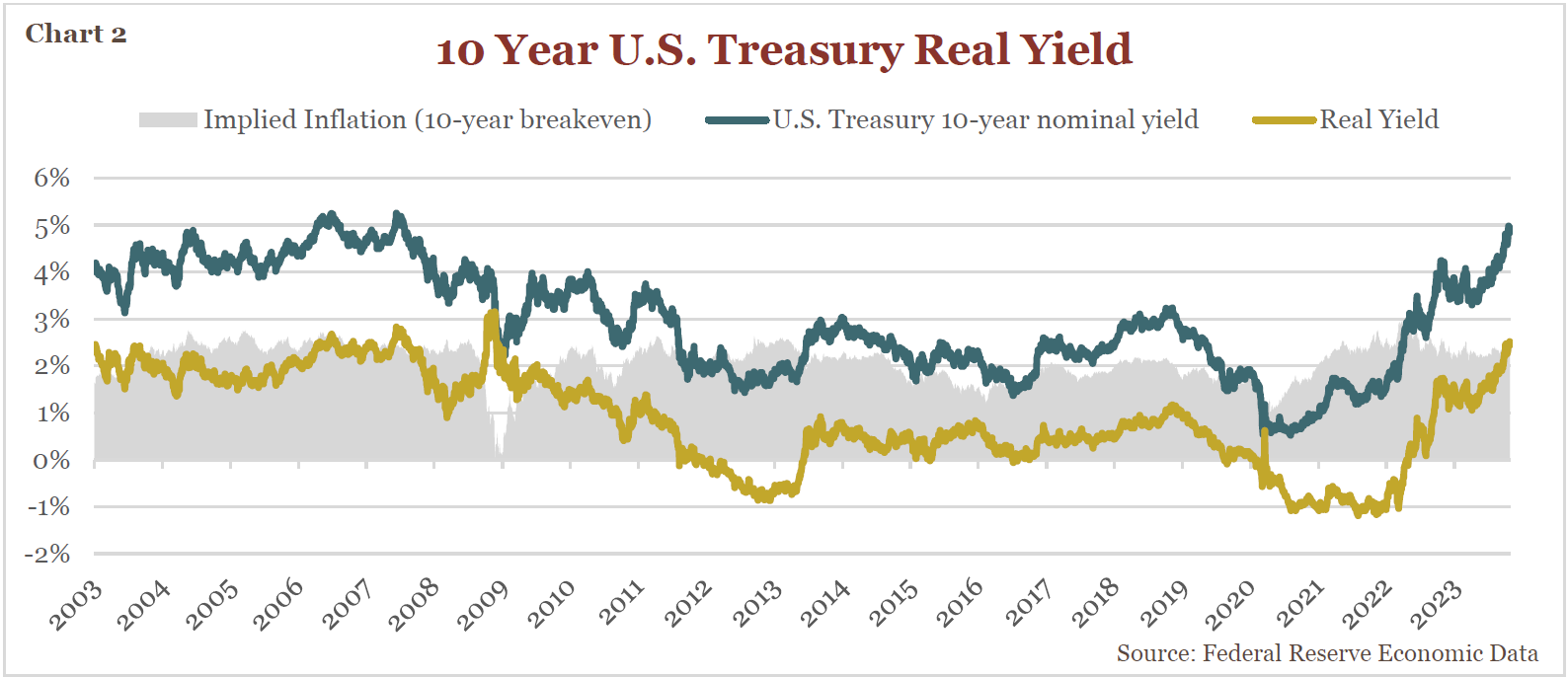

Inflation expectations, often measured by the breakeven inflation rate, play a pivotal role in determining long term bond yields. If inflation expectations rise, long-term interest rates will adjust to compensate. Inflation expectations can be calculated by subtracting the yield on a conventional Treasury security from that of a Treasury Inflation Protected Security (commonly referred to as TIPS), whose yield is indexed to inflation. The difference in yield is considered a gauge of the market’s inflation expectations because it indicates the inflation rate at which TIPS investors would earn the same real return as conventional Treasury investors or “breakeven”. After soaring to new highs in early 2022, the breakeven inflation rate has steadily retreated, currently at 2.33%, slightly above the average since 2004. With inflation expectations seemingly under control, it is evident that the recent move in long-term bonds is being driven by an increase in real yields (see Chart 2).

Real yields can be thought of as the annualized return on an investment after adjusting for inflation. Their importance resides in their ability to unveil market expectations pertaining to future economic growth and the course of monetary policy. For example, real yields turned negative in early 2020, when market participants were worried about a Covid recession, but reversed course coming out of the pandemic. Rising long-term real yields could also suggest investors are demanding a higher term premium, or simply put, additional yield to accept heightened uncertainties in the coming decade. While pinpointing exactly what is driving real yields higher is not straightforward, two factors stand out – Monetary Policy and Government Debt.

One prominent factor is the market’s growing realization that central bank policy rates, commonly referred to as the Federal Funds rate in the U.S., will need to stay higher for longer. At the beginning of 2023 market participants anticipated just two additional 0.25% rate hikes and many were even expecting rate cuts by the end of the year. Instead, a resilient U.S. economy driven by steady hiring and consumer spending (thank you Taylor Swift) forced the U.S. Federal Reserve to remain vigilant. So far this year, the Fed implemented four 0.25% rate hikes and believes rates will need to stay north of 5% in 2024 to reach their objective of stable 2% inflation. This “higher for longer mantra” has not only taken hold in the U.S. but is also being echoed by the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, the Bank of Canada, and the Reserve Bank of Australia.

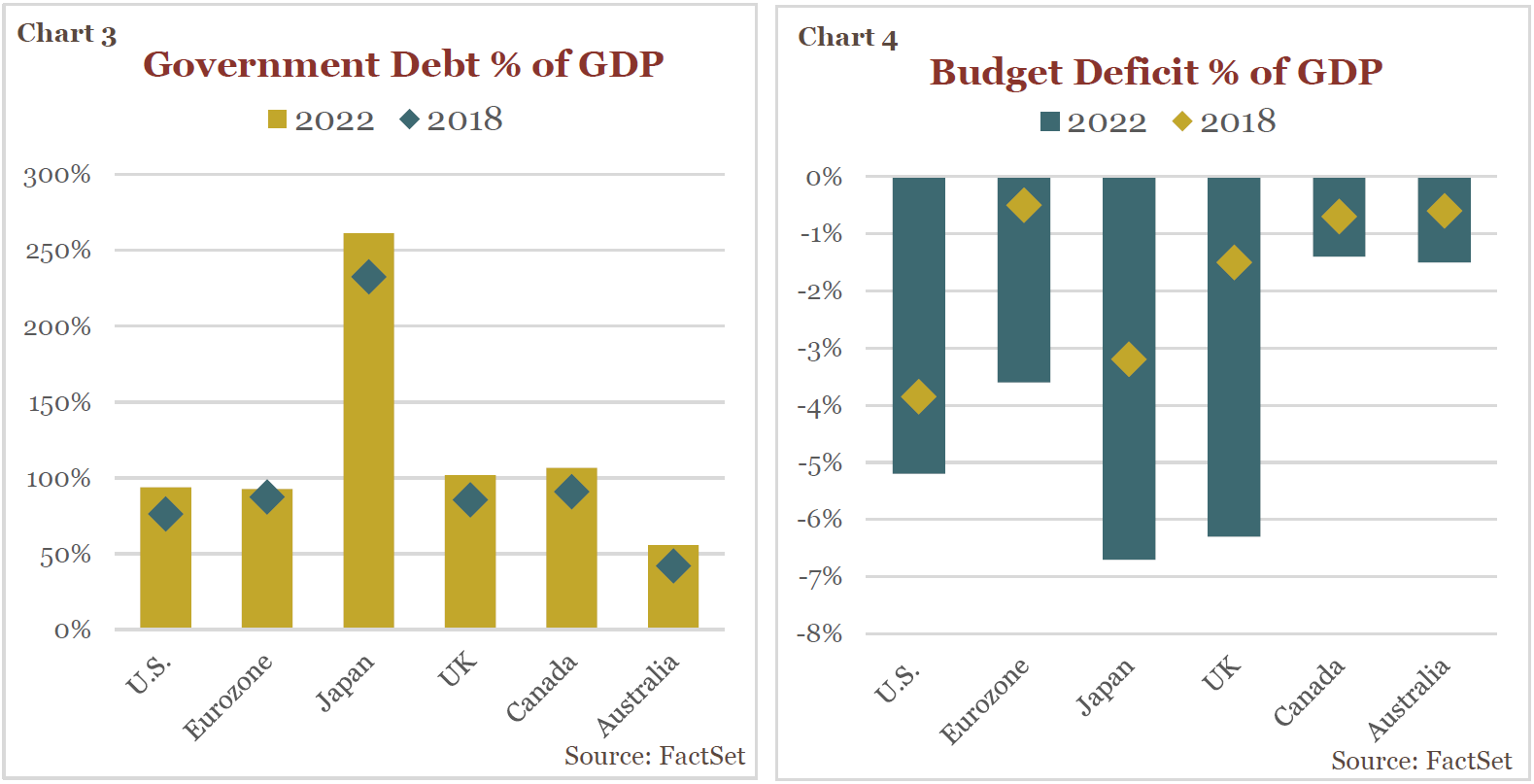

Another crucial element likely pushing real yields higher is the sharp climb in government debt. Government borrowing surged in the aftermath of the pandemic and many advanced economies are confronted with debt to GDP (Gross Domestic Product, i.e., the size of the economy) ratios at or near 100% (see Chart 3) alongside budget deficits approaching or exceeding 5% of GDP (see Chart 4). And the prevailing trajectory is not improving. For instance, the U.S. recently report a budget deficit in

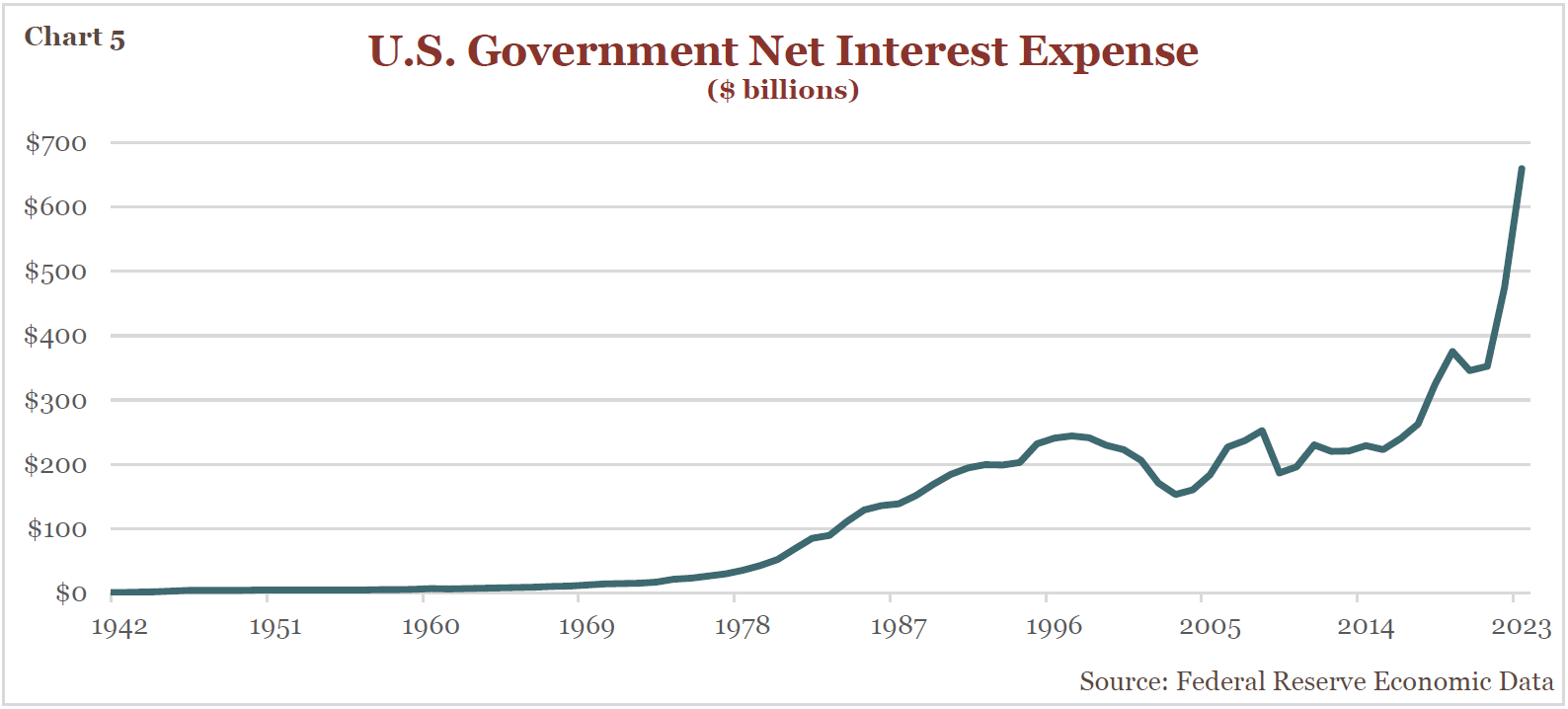

2023 of $1.7 trillion, or 6.3% of GDP, a 23% increase from a year ago. The growing debt levels are compounded by short-term interest rates exceeding 5%, elevating the cost to refinance and service existing debt. The U.S. federal government closed out fiscal year 2023 spending $659 billion on interest payments (see Chart 5), up from $476 billion in 2022, and $352 billion in 2021. Based on current interest rates and spending projections, net interest expense will exceed defense spending by 2025 and become the largest federal spending program by the end of the decade.

This increased government spending and higher refinancing costs are unfolding against the backdrop of a shift in monetary policy by the Fed, the U.S. government’s most reliable buyer.

To help drive down interest rates and stimulate the economy during the pandemic the Fed purchased nearly $3.5 trillion of Treasuries securities (i.e., quantitative easing), or nearly 50% of all newly issued U.S. government debt from January 2020 to June 2022, but has since resorted to quantitative tightening to combat high inflation. Currently, the Fed is reducing its balance sheet holdings by rolling off approximately $60 billion in Treasury securities each month, which when combined with the $1.7 trillion budget deficit, equates to ~$2.4 trillion of Treasury supply the private market must absorb over the next year. In contrast to the Fed, the private market is a price sensitive buyer who requires higher real yields based on the unsustainable path of government spending.

While rising long term yields will aid central banks in their fight against inflation, they will also weigh on GDP growth in the coming months. Perhaps the most salient consequence is the pressure higher interest rates will put on government budgets. Continuing to run massive deficits in the face of higher rates is poised to compound the already burgeoning debt problem, as interest payments on the debt will consume an increasing share of government spending. If sustained, this will diminish governmental flexibility in the face of future economic downturns as well as limit government’s capacity to fund critical programs such as infrastructure, education, research and development and healthcare.

Global Markets is published as a service to our clients and other interested parties. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. Individuals should seek advice from their own legal, tax, or investment counsel; the merits and suitability of any investment should be made by the investing individual. References to specific securities, asset classes, and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only. Actual holdings will vary for each client, and there is no guarantee that a particular account or portfolio will hold any or all of the securities listed. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Investments carry risk and investors should be prepared to lose all or substantially all of their investment.