,

December 31, 2018

Stock market returns in the eurozone as measured by the MSCI EMU1 index fell 19% in 2018, pulling back on the 26% gain in 2017. Primary drivers for the lagging performance are slower growth expectations, currency pressure, and uncertainty driven by Eurosceptic politicians.

Euroscepticism refers to someone who opposes increasing powers of the European Union (EU). Threats to leave the EU or defy EU rules are common expressions of Euroscepticism. However, the consequences of rebelling against or separating from the EU would be greatest for those 19 countries that have adopted the common currency (the eurozone). Like a dog that hates its leash but knows putting it on means going for a walk, countries accept the monetary tether knowing it allows them to compete with economies much larger and more powerful than their own.

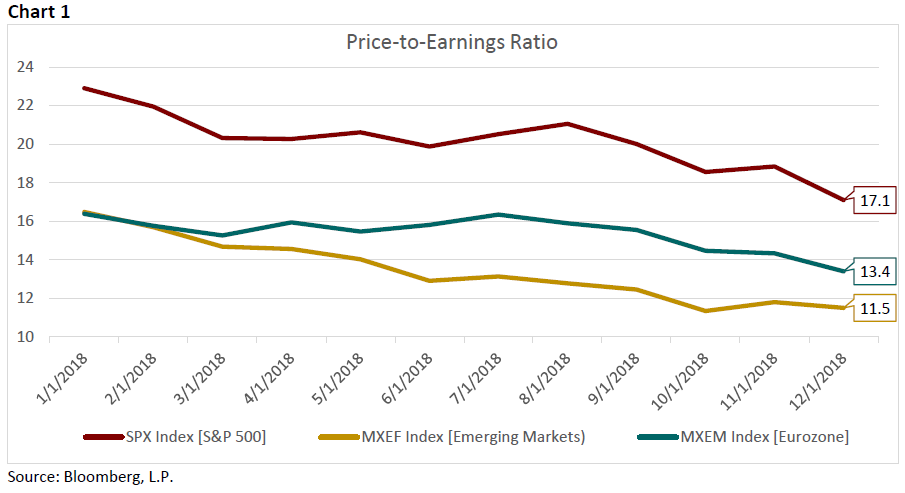

Politicians in eurozone countries with large national debts publicly boast they will violate agreements with the EU regardless of economic consequences. As a result, some investors who are convinced the risk is real sell their stock at a discount. Eurozone price-to-earnings ratios are only slightly higher than those of emerging markets, meaning eurozone stocks are only slightly more expensive (Chart 1). This suggests investors believe eurozone companies face almost as much risk as emerging market companies. However, emerging market countries often lack rule of law and offer foreign investors very little predictability. Notably, price-to-earnings ratios are lower for both eurozone and emerging market stocks than U.S. stocks. A review of concessions made by the most Eurosceptic political leaders in the most indebted countries in the eurozone suggests the risks may be overstated; therefore, stocks may be discounted.

In June, a new coalition government was formed in Italy by two extreme parties, which both identify as Eurosceptic. Campaigns held promises to lower taxes, increase pension benefits, and introduce an expensive basic welfare program. In 2018, Italy’s debt was 131% of its GDP, compared to 87% for the entire eurozone (Eurostat) and 76% for the U.S. Despite the alarming debt level, the new government set the budget deficit target to 2.4% of GDP. That amount clearly defied EU budget rules, which oblige Italy to reduce its debt.

Italian stocks measured by the FTSE MIB2 Index fell 25% from their peak prior to the formation of the coalition government through October when the audacious budget was submitted to the European Commission (EC). This demonstrated investors’ fear Italy would fund the lifestyle of its people with more debt rather than introducing reforms to encourage business and job growth. The EC rejected the budget and reacted with threats of fines if it was not revised. In Rome, politicians committed passionately to the budget in the press while they negotiated in the background with the EC. Ultimately, leaders in Rome caved and agreed to a budget that cut spending by roughly eight billion dollars to 2.0% of GDP. The EC called their bluff.

The situation in Italy echoes that of Greece in 2015 when newly elected Prime Minister, Alex Tsipras, led a campaign to reject reforms imposed by the EU and IMF since Greece began receiving bailouts in 2010. In need of another bailout, the EC and IMF offered Greece a joint proposal. Tsipras initiated a referendum on July 5, 2015 to let voters decide to accept or reject the bailout conditions. They were rejected. “Grexit” fears shocked markets as investors contemplated the disaster Greece would face refusing the much-needed cash and possibly departing from the euro and EU. Within eight days of the vote, Tsipras’ government accepted a bailout with conditions even more strict than the ones rejected by referendum. Tsipras realized that the only alternative to being “leashed” was letting his country run into traffic, so he chose the leash. The reforms he accepted have been effective.

Since 2015, Greece has reduced their spending and runs a budget surplus. Unemployment has fallen from 24.8% in July 2015 to 18.6% as of September 2018, and total employment is projected by the OECD to continue growing. In 2017, the country experienced its first year of GDP growth since 2008. Data from 2018 reflects a continuing trend.

Italy and Greece have a long journey ahead reducing their debt levels and may never become a great example of growth and stability. However, they demonstrate the monetary leash is effective at keeping defiant new leaders in check.

While the EC arm wrestles with individual Eurosceptic leaders, the European Central Bank (ECB) must focus on the direction of the eurozone as a whole. In December, policymakers at the ECB decided to end its asset-purchasing program. This signaled a positive outlook from the central bank. It implied EU support could withstand the Eurosceptics, and the eurozone economy was growing enough to justify reducing stimulus. Eurozone inflation reached and hovered around the ECB’s 2.0% target in the second half of 2018 (Eurostat). Unemployment has been falling steadily from its 12.1% peak in 2013 to 8.1% in the third quarter of 2018. GDP per capita has continued to climb in that same time. The dollar’s increased strength in 2018, which had crippling effects on some emerging economies like Argentina and Turkey, had a muted effect on the eurozone where earnings stayed stable.

There is still room for expansion, although the rate and duration are uncertain. Fortunately for investors willing to take the long view, eurozone stocks are selling at a 22% discount to the S&P 500. Even slow growth on top of that discount could result in generous returns. As long-term investors, we hope to find value by maintaining a disciplined approach, while others make impulsive decisions rooted in fear or euphoria. Keeping an allocation of our clients’ equity portfolios in foreign companies allows us to take advantage of opportunities abroad, which are currently cheap relative to the U.S. due in part to exaggerated risks of opposition to a more unified Europe.

1 Morgan Stanley Capital International European Economic and Monetary Union 2 Financial Time Stock Exchange Milano Indice di Borsa

Investment Insight is published as a service to our clients and other interested parties. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.