,

June 30, 2019

With innovative companies like Uber, Lyft, Pinterest, Airbnb, Zoom, and Beyond Meat going public in recent months, it feels like 1999 all over again. Except this time is different. Investors who remember the tech bubble of 20 years ago are no longer willing to buy a startup just because its name ends in “dot-com.” Instead, some investors are putting a premium on businesses with long-term expansion or disruption potential, hoping if they invest now, the business will grow and realize large profits later. Other investors are uncertain about getting involved at all in the new wave of initial public offerings (IPOs).

In GHPIA’s analysis of the current IPO mania, we noticed two trends. One is the dramatic reduction in the number of publicly traded companies. The other is the rise of a new breed of company, the Unicorn – a privately held startup valued at over $1 billion.

The current IPO mania feels like 1999 all over again. Except this time is different.

Since the Dutch East India Company became the first public company in 1602, public companies have been a fixture of capitalism. Selling shares to the public allows companies to raise money from the broadest group of investors. In recent years, however, the universe of public companies shrank. New businesses offered shares to the public at less than half the rate they did during the 1980s and 1990s. Mergers and acquisitions eliminated even more public companies.

In 1999, there were 7,229 public companies; as of 2018, there were only 4,397 companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges. The decline is often blamed on regulation – most notably, the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley legislation, which addressed public company accounting frauds in the 1990s. However, regulation alone does not account for the steep drop.

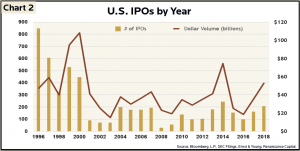

The number of listed companies peaked during the late 1990s, when hundreds of startups cashed in on the rise of the Internet by going public. Many of these companies disappeared during the subsequent dot-com bust, because they never earned a profit and were founded on dreams, not solid business plans.

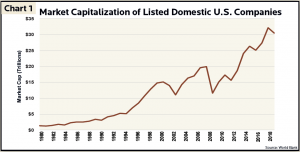

Regardless, the public company is far from dead. While public companies decreased in number, those remaining grew in size. Even as the number of exchange-listed companies declined, their investable value increased (Chart 1).

Although the number of companies filing for IPOs is significantly smaller than in 1999, the companies are larger and more mature (Chart 2). The median age for tech companies going public in 1999 and 2000 was 5-6 years, compared to 10 years in 2018. Median sales, meanwhile, were about $12M then, compared to $173.6M last year. Tech startups are awash with private funding and can now afford to take their time going public. Like their predecessors 20 years ago, however, IPO companies in 2019 are still unprofitable.

Consider the example of Beyond Meat, the plant-based burger company. On its first day, Beyond Meat opened trading at $46/share, which was 84% higher than its IPO price. It extended its gains to close that day at $65.75/share, making the company the best performing first-day IPO in two decades. At this writing, the company is selling for 560% over its IPO price.

Investors still have an appetite for unprofitable companies.

While Beyond Meat successfully grew its revenue over the past several years, it has yet to make a profit. The company reported a net loss of $29.9M on revenue of $87.9M in 2018. For its $9.65B market value to justify a buy recommendation from GHPIA, revenue would need to exceed $1B while maintaining healthy profit margins.

In a world where the FAANG companies (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google) went public without positive cash flows and earned investors triple-digit growth, many investors believe each new company going public could be the next big winner. This IPO surge could leave wreckage behind. Notably, Lyft’s $911M annual loss in 2018 was greater than that of any other American startup; that is until Uber went public just six weeks later. Decade-old Uber is losing more than $1 billion per quarter. Lyft’s current share price of $64 is down more than 10% from its IPO price. These stock returns may turn positive, but GHPIA’s investment philosophy is to invest in profitable companies selling for reasonable prices.

Not every disruptive company needs to enter the IPO circus to raise capital. These days, easier access to venture and private equity capital reduces the pressure for companies to go public to fund growth, creating a herd of Unicorns. The number of Unicorn sightings in the United States has risen sharply. In 2013, there were just 38 Unicorns in America. Now, the Unicorn leaderboard lists 156 companies in the U.S. and a total of 326 internationally. As these companies with near mythical valuations search for public capital, there is a full pipeline of late-stage startups likely to deliver new offerings to the markets. Even if these Unicorns eventually go public at inflated valuations, the number of companies and their valuations are unlikely to match the IPO frenzy of the late 1990s.

At GHPIA, investing in these highly speculative and risky IPOs violates our investment philosophy. We hope these Unicorns mature into companies with real earnings, but we will avoid disaster if profitability remains a fantasy. Adding new companies to the U.S. market is positive, even though many new IPOs are unprofitable and unlikely investments for GHPIA. This IPO party does not have as many young, new participants, and we do not anticipate a hangover like we experienced in the 2000s from the dot-com bubble.

Investment Insight is published as a service to our clients and other interested parties. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.