December 31, 2018

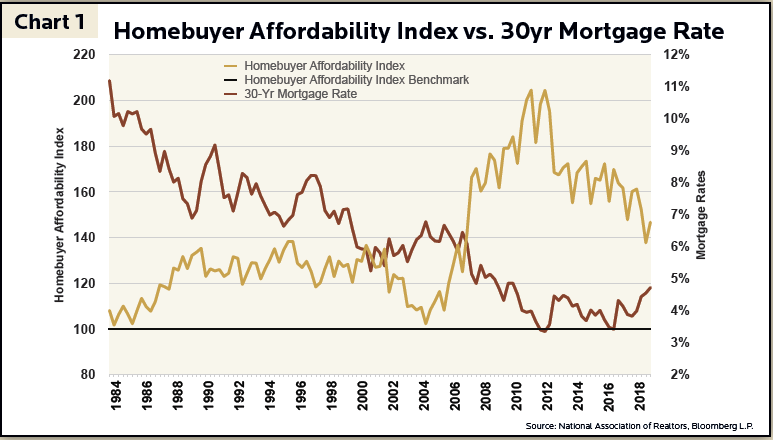

Home ownership is part of the American dream, but recent headlines suggest achieving this dream is becoming more expensive. Following the Financial Crisis of 2008, housing affordability reached a record high in 2012 (Chart 1). During this period, home prices bottomed (from the prior peak in 2007), and the average 30-year fixed rate mortgage dropped to a record low of 3.66%. As home values and interest rates decline, affordability increases and vice-versa.

Since affordability peaked in 2012, the median home price in the U.S. increased at an annualized rate double that of wages. In addition, mortgage rates rose to 5%, increasing monthly payments for new homebuyers. These events are blamed for the fall of new- and existing-home sales in the second half of 2018. Fortunately, based on the Homebuyer Affordability Index (HAI), the American dream is still possible. If the HAI reads 100, the median household income is just enough to purchase a median-priced home. The HAI currently sits at 147, indicating a family earning the median income has 147% of the income necessary to buy a median-priced home.

However, even if homes are more affordable, homebuyers may struggle to secure mortgage credit, a key factor not represented in the index. Access to mortgage credit remains tight for many borrowers due to post-Financial Crisis regulations. Further loosening of regulations may be needed to support the strong real estate market.

The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage significantly increased homeownership in the U.S. Prior to 1930, the typical mortgage term was 5 years, carried a variable interest rate, required a high down payment (50% or more) with a balloon payment at the end of the term. Instead of paid off, loans were usually refinanced annually.

Rigid mortgage terms amplified foreclosure rates during the Great Depression. Borrowers had neither the cash nor home equity to pay their loans back. Fear of taking on more losses caused banks to halt lending, exacerbating the problem. At the height of the Great Depression, 10% of homes faced foreclosure, compared to a peak of 4.6% of homes in 2010 following the Financial Crisis. In response, the federal government created two important organizations [the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1933, later replaced with the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in 1936]. The HOLC purchased and converted one million mortgages into fixed-rate, longterm mortgages. Then, the FHA purchased these loans and provided a guarantee to investors that the loans would be repaid in full. This combination took risk off bank balance sheets and provided banks with cash for further lending.

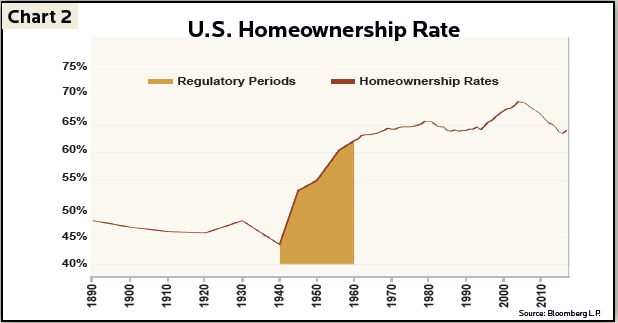

Three more key developments expanded access to housing. At the end of World War II, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 passed, allowing veterans to obtain mortgages with lower down payments. Shortly thereafter in 1948, the FHA raised the maximum term to 30 years from 20 years. Lastly in 1956, the FHA reduced the minimum down payment to 5% from 20%. Over 20 years of housing reform later, the homeownership rate rose drastically from 44% in 1940 to 62% in 1960 (Chart 2).

The process of buying mortgages and repackaging them into investments carries big implications for risk taken by banks. In 2017, the two biggest government-backed mortgage financers, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, purchased an estimated 50-60% of all mortgages originated. Mortgages considered too risky to purchase were retained on the balance sheets of banks. In the post-Financial Crisis world, Fannie and Freddie require stricter lending standards for mortgages purchased, and banks are required to hold more reserves for risky assets held. This has caused banks to take less risk, creating tighter access to mortgage credit.

After 2008, lenders required higher down payments and favored higher income earners to improve mortgage credit quality. More importantly, the average credit score for a loan purchased by Fannie and Freddie jumped from 710 in 2001 to 760 by mid-2012. The percentage of new borrowers with credit scores below 660 (considered subprime) dropped from just above 30% of new mortgages to roughly 10% over the same time. This is likely the result of higher foreclosures directly following 2008. Foreclosures stay on credit reports for seven years. While foreclosures peaked in 2010, it took until mid-2015 for foreclosures to fall below 2% (still high by historical measures). These changes improved the mortgage credit quality of loans purchased but reduced the number of eligible mortgage applicants.

Families fortunate enough to obtain mortgages prior to the run-up in real estate prices and interest rates lack incentive to obtain new mortgage terms. This was evident from mid-2013 through 2014, when mortgage applications fell. In response, Fannie and Freddie loosened rules surrounding mortgage requirements, reversing prior tightening policies. They reduced the minimum down payment and later reduced the income required to qualify for a mortgage. Following these changes, the surge of mortgage applicants highlighted demand existed for those with less resources.

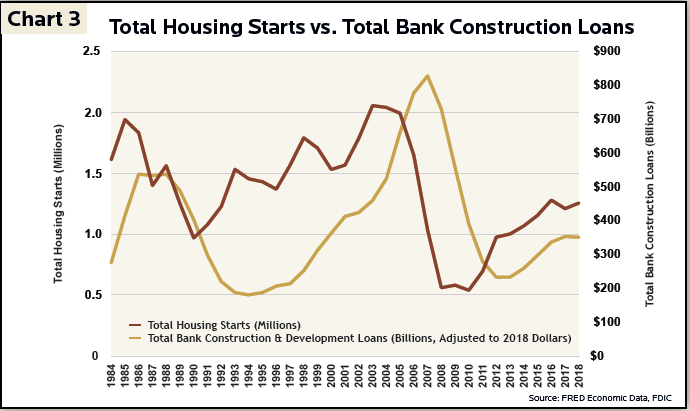

New-home builders also struggled to gain access to credit, resulting in higher home prices due to the lack of new supply. New-home construction (housing starts) and construction loans took a severe dive following the Financial Crisis (Chart 3). Banks required more capital reserves for construction loans due to their risky nature. Also, banks are less willing to lend up to 100% of the financing needed, which was customary prior to the Financial Crisis. This occurred during a time when construction material costs rose three times faster than inflation, and a lack of qualified labor required a premium for construction workers.

The evidence does not appear to signal a looming housing downturn. To the contrary, home affordability remains elevated with a current reading well above 100. Recently, wages have been growing faster than home prices, and we are still in a low interest rate environment. While the affordability of housing remains strong, this does not mean everyone benefits.

Access to credit is the driving force behind the rise of homeownership. Pre-Financial Crisis regulations were too loose creating malfeasance and predatory lending. In response, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction, but we are seeing signs restrictive post-crisis rules are loosening. Greater access to credit should provide a new wave of homebuyers and homes built, adding strength to the real estate market.

Investment Insight is published as a service to our clients and other interested parties. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.