,

March 30, 2017

Once upon a time, an entrepreneurial little girl named Goldilocks started three banks. Raising $1 billion from a stock offering to investors, Goldilocks established Too Cold Bank, Too Hot Bank and Just Right Bank.

Goldilocks’ first idea was to simply take the $1 billion equity capital and make mortgage loans to homebuyers. Since Too Cold Bank did not accept deposits, it avoided most banking regulations. Goldilocks hired staff to evaluate borrower credit and collateral, process payments, and manage delinquent collections or foreclosures if necessary. Within a few months her terrific team loaned their $1 billion to several thousand borrowers. Like other banks they charged 4 ½% interest and watched the revenues roll in.

After her first year in operation, Goldilocks was pleased to see revenues at Too Cold Bank were $45 million. All customers paid on-time and in-full. Overhead was modest so Net Income After Taxes was $22 million. “Wow”, thought Goldilocks, “our profit margin is nearly 50%. Who can beat that?!” She proudly mailed financial statements and dividend checks to her investors.

To Goldilocks’ surprise she received angry phone calls from her investors. They wanted to know why their return on investment was only 2.2% (i.e. $22 million after-tax profit on $1 billion of capital). They threatened to liquidate Too Cold Bank and put their capital to work elsewhere if Goldilocks could not deliver higher returns.

After a few calculations, a chastened Goldilocks realized Too Cold Bank would need to charge substantially higher interest rates to deliver reasonable returns to her investors. Goldilocks needed a better business model, and she needed it fast.

Now rechristened as Too Hot Bank, Goldilocks was ready with a new business plan. This time Goldilocks accepted deposits. Deposits were like inexpensive loans to her bank that she could relend to homebuyers without raising additional equity capital. She particularly loved interest-free checking accounts.

Attracting deposits involved higher costs, such as branch offices staffed with tellers and ATMs. She also expanded her operating staff to handle higher loan volumes. Given these higher costs Goldilocks wanted to expand deposits as much as possible.

Over time Too Hot Bank gathered $50 billion in deposits, including checking accounts, savings accounts, and CDs. Too Hot Bank now paid an average 1% interest on many of these accounts. From prior experience Goldilocks realized she only needed to keep about 2% of her deposits in cash to meet average daily withdrawals, freeing up more funds for lending.

To attract more mortgage borrowers, Too Hot Bank started paying commissions to brokers, further cutting into interest income. Despite higher costs to attract deposits and loans, Too Hot Bank still earned an average 3% on its mortgage loan portfolio. Even though the original equity investment remained $1 billion, revenues were now $1.4 billion! Rather than $22 million in After-Tax Net Income at Too Cold Bank, Too Hot Bank generated a $400 million profit. When her investors received their 40% annual return, they could not believe their eyes.

Unfortunately, in her rush to expand, Goldilocks forgot to maintain a sufficient capital cushion against default and loss. Even when the economy is healthy, some borrowers default or require expensive foreclosure. Very modest credit costs soon wiped out her entire profit, pressured her liquidity and threatened insolvency. Some nervous depositors withdrew their funds, and her equity investors lost money. Goldilocks learned she needed to keep cash reserves in case of large withdrawals. She also needed to maintain sufficient equity capital relative to total bank assets to guard against loan losses.

Goldilocks realized she could not deliver returns to her equity investors without some degree of risk, but too much risk increased the chances of bankruptcy. Her new bank – Just Right Bank – tried to maintain equity capital relative to mortgage loans in a healthier range. Her bank still might fail if their loan underwriting was inaccurate or if the economy was particularly bad, but chances of survival remained quite high.

Goldilocks realized her experience also applied to the entire financial system. Extremely safe financial institutions would require very high interest rates, produce insufficient credit and shackle the economy with sluggish growth. On the other hand, risky financial institutions would juice economic growth with generous credit at low interest rates while increasing the chances of financial calamity. A healthy financial system, however, accepts some degree of risk in exchange for ongoing economic dynamism.

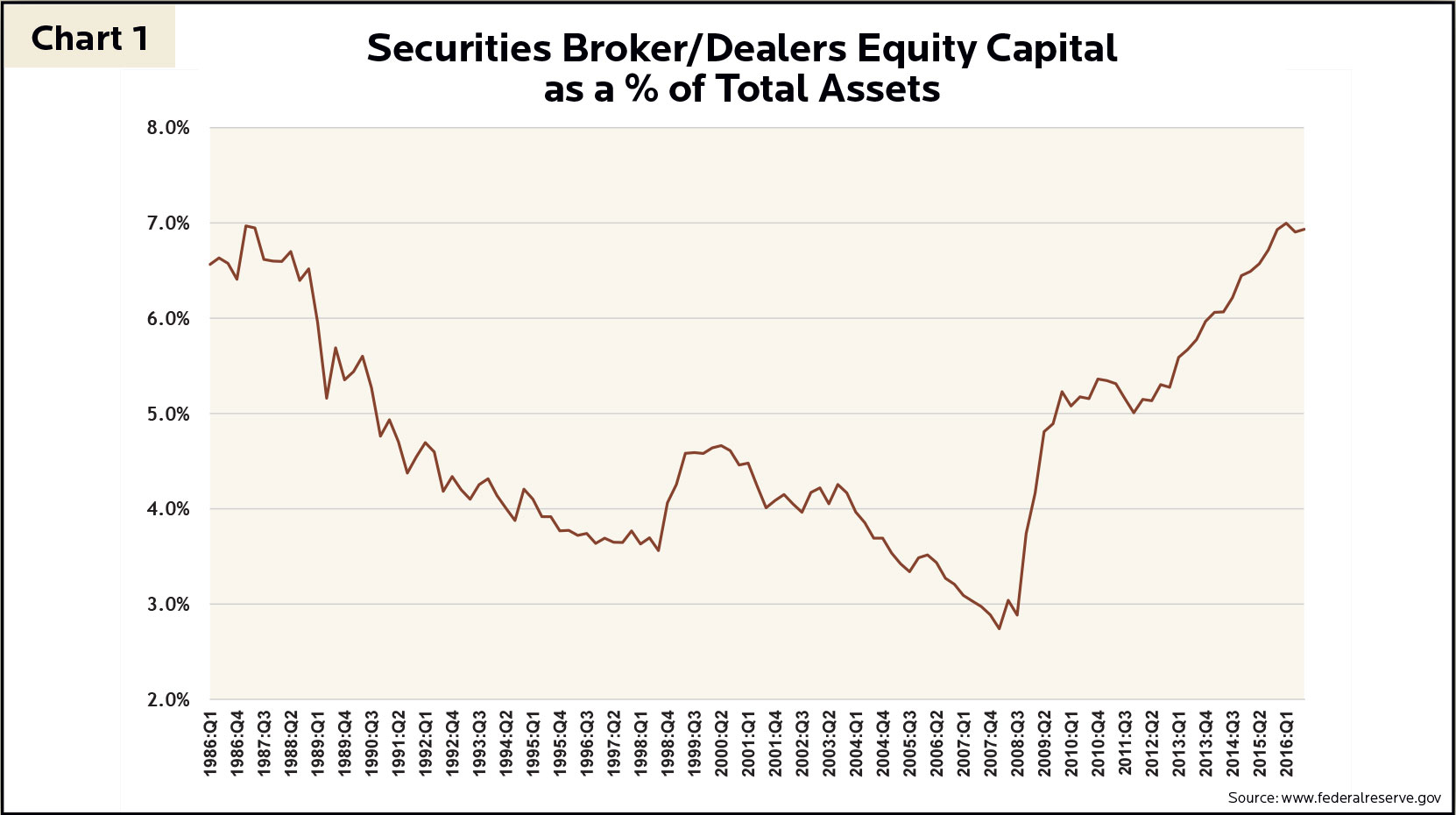

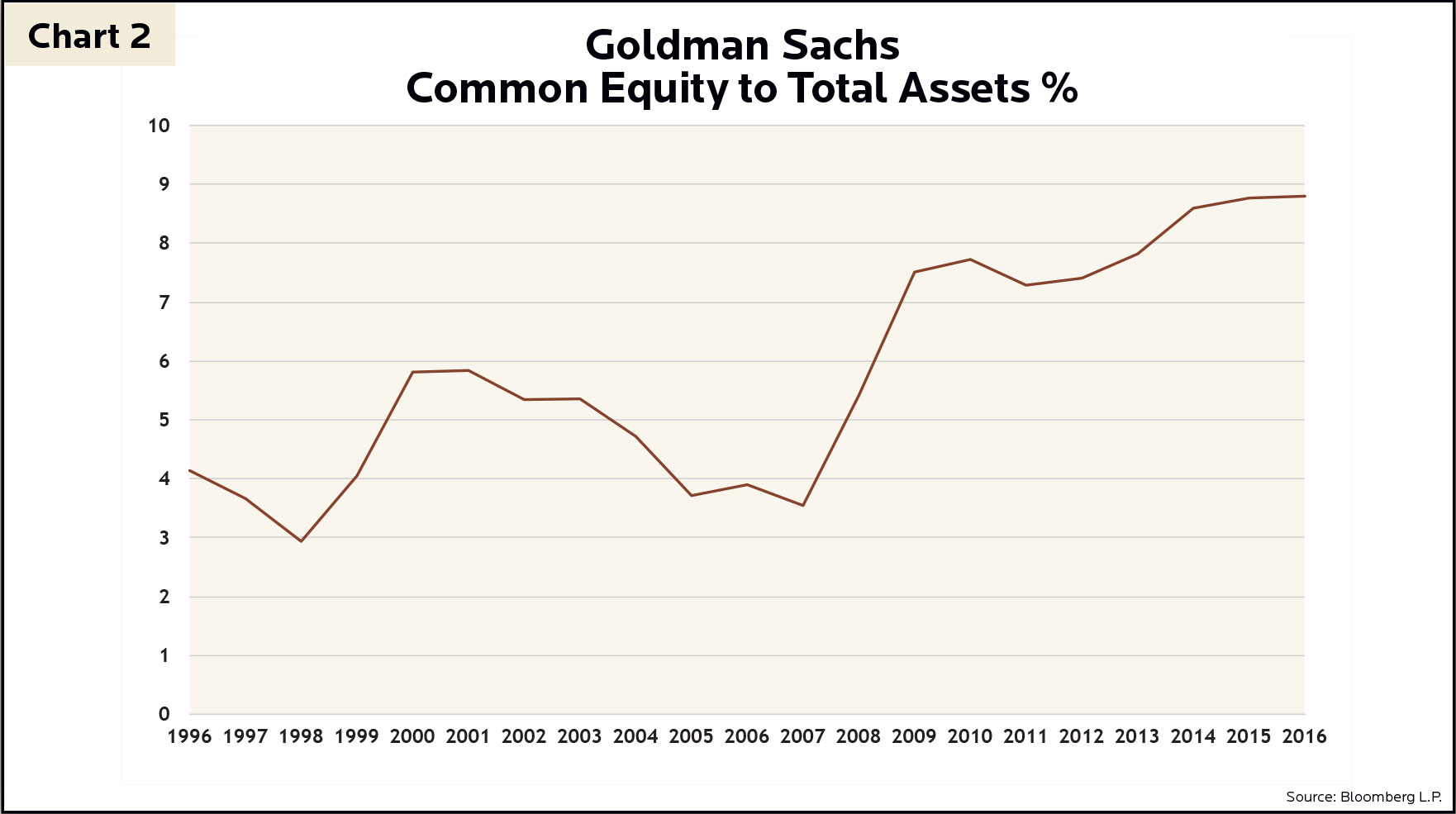

Modern banks are more complex than the simple examples above, but the principles remain the same. In the years preceding the financial crisis, the riskiest financial firms were investment banks underwriting mortgage securities such as Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, and Merrill Lynch. The most leveraged failed, but the survivors spent the past 8 years rebuilding their equity capital cushion. As you can see in Chart 1, equity capital for the securities industry is back to 30-year highs. Chart 2 depicts the same ratio for a leading player in this industry segment: Goldman Sachs.

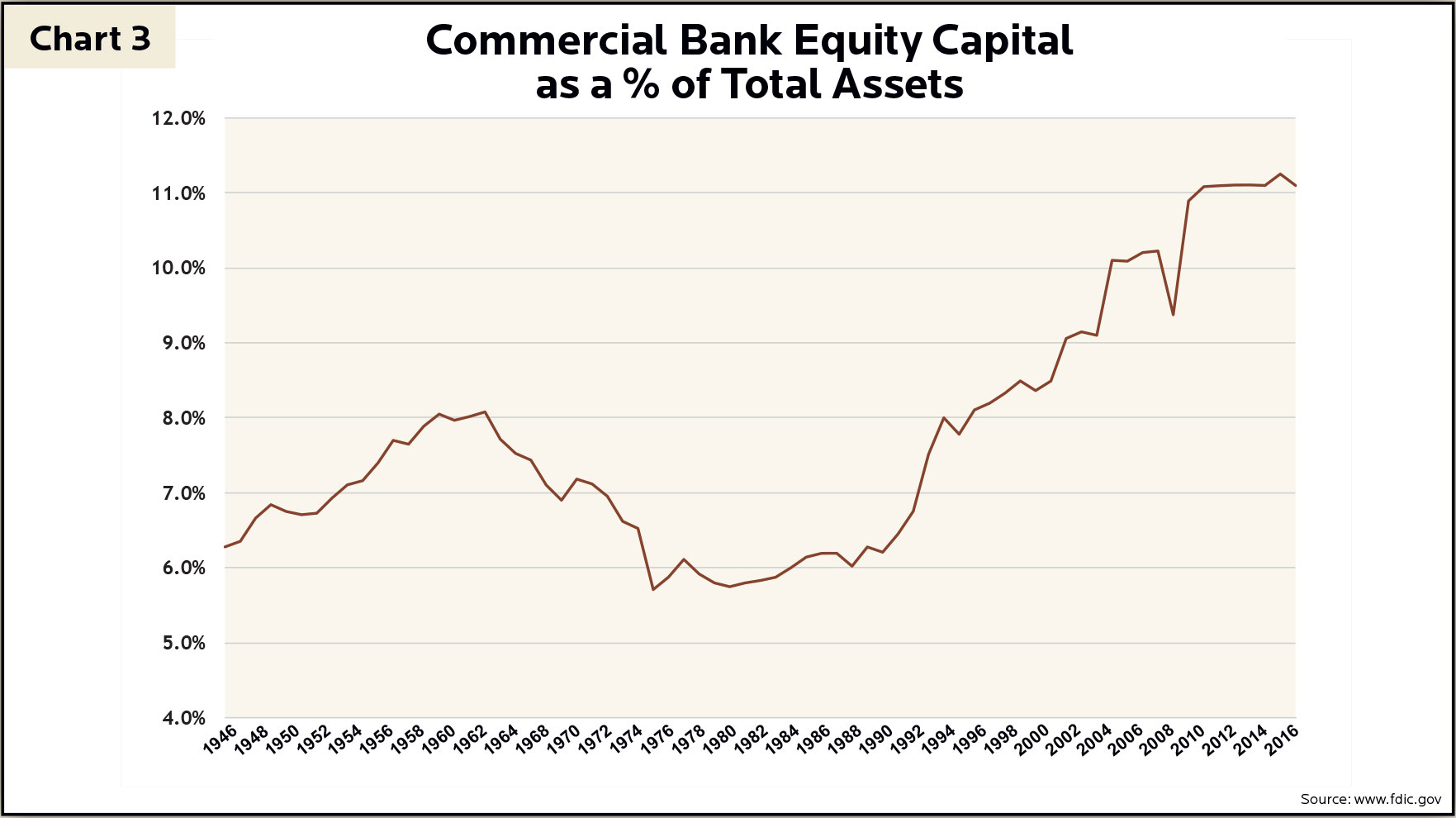

Traditional commercial banks such as Wells Fargo and U.S. Bank accept deposits and extend loans just like the banks Goldilocks started. After the Savings and Loan Crisis in the 1980s, regulators required higher equity capital ratios. Even with a few high-profile exceptions, most commercial banks survived the 2008 financial crisis due to this capital cushion (with an added boost from the Federal government). As illustrated in Chart 3, Commercial Banks now carry very high equity capital ratios by historical standards.

Some politicians and regulators argue that the U.S. financial system is still too risky. They want banks and other financial firms to resemble Too Cold Bank. Goldilocks understands, however, that a very safe financial system would likely produce economic stagnation. Some swashbuckling financiers remember fondly their days at Too Hot Bank. They miss their fat paychecks, and they want the government to get out of their way. They understand the economy could grow much faster with greater financial freedom. Goldilocks is wary; Too Hot Bank was precarious and scary. She believes letting the financial system leverage up as before would run unacceptable risks. After reviewing Charts 1, 2 and 3, Goldilocks sees that the financial system is no longer undercapitalized as it was 10 years ago. In fact, capitalization is now at historic highs. Goldilocks listens to the heated rhetoric on television, but thinks to herself “perhaps allowing financial firms a little more flexibility now that they are sufficiently recapitalized might be just right.”

Investment Insight is published as a service to our clients and other interested parties. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.